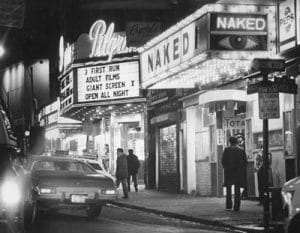

The gig was on Tremont Street in an area called the “Combat Zone.” It was known as a rough area, though I never had any problems. I would take the subway that ran underneath Boylston Street from the Berklee dorm on Mass Ave to be at the club for a 6pm start. When the gig ended at midnight, the subway had stopped running, so it was a long walk back to the dorm. All this meant that I didn't get much sleep, but I managed to get straight A's, except for an "F" failing grade in piano lab, since I skipped the class entirely.

Mike and I played as a duo, piano and drums. We were at the side of a very narrow stage behind the bar, so those sitting at the bar could easily watch the dancers. The piano was an old, out of tune, Wurlitzer spinet. We would play 6 hours, one-hour sets with 15-minute breaks, 7 nights a week. We played up to midnight as Boston law allowed. After a few weeks, the law was changed to 1am, only on Saturday nights, but we always started at 6.

We played for the dancers, singers, and in-between the acts. Mike was only 16 years old and a fantastic drummer. Musicians from nearby clubs would come in to see us, mostly to watch Mike play. We made $100 a week each. When we found out duo across the street was making $150 a week for only 6 nights, we were jealous!

I was geeky and very naïve, but slowly learning. I played all the jazz and pop tunes from memory, so I was easily able to watch the dancers. Boston's puritanical laws allowed only limited nudity, no bare nipples. But when the dancers turned their back to the audience to make costume adjustments, we could see pretty much everything. A black dancer could spin her boobs in opposite directions (nipples carefully covered). Amazing!

I took a liking to one of the young dancers, though I was too shy to ever talk to her. One of the regular customers noticed me staring at her and said, “So you like her, eh? Do you know she's a lesbian?” “Lesbian?” I said, “What's that?” He explained and I was getting the idea. But a couple days later, she asked me to sit next to her at the bar. Without saying much, she pulled toward her and gave me a long, deep, french kiss. She said, “I would love to take you home with me tonight, but it wouldn't be right.” I was speechless.

One of the performers was a singer who seemed very old, but was probably in her 50s. In her younger years, she was a dancer. She told a story about surviving the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in Boston in 1942 which killed 492 people. As the fire raged and the tragedy progressed, she didn't know what to do, so she kept dancing. She passed out from the smoke, and her family later found her in the morgue.

She and Joe, the manager/bartender at the Caribe Lounge, had a long history together. He was forced to fire her in favor of a younger performer. She was devastated and sang “Have a Good Time,” the Ruth Brown song, with the sarcastic line “don't worry about me, forget I'm alive.” Joe was irritated and bought me a beer at the end of the night. He said he hated to fire her, because she had a good heart. “In the old days,” he said, “she would do anything for me, even sleep with me if I needed some.” Today that's called “friends with benefits.” I was learning.

At Berklee, my roommate, a drummer, was looking for a gig. Somehow he got the number of Otis, the mysterious voice offering gigs on the dorm's hallway pay phone. Otis told Andy he'd heard they were having trouble with the drummer at the Caribe Lounge. Mike had, in fact, mouthed off to the bartender a couple of times over the past few days. Andy, of course, knew that I was working every night, but he didn't know the name of the club. One night at Caribe I saw Andy come in the door. He glanced at us, then immediately left, because he didn't want to stir things up. Eventually things settled down and Mike kept his job.

Another Berklee classmate had turned me on to smoking pot. Eddie, a skinny but tough New York City Italian kid, rolled a skinny joint and took me to the park near the school. After a couple of puffs, I didn't notice any immediate effect. But as we started walking back, I looked up at the Prudential Building and could see electrical waves of light, like rippling water, emanating from atop the building. I felt loopy and started dancing and jumping up and down. Eddie smirked. When I got back to my dorm room, I listened to Shostakovich's 5th Symphony. I could “see” the notes pouring out of the speakers as I laid still on my bed. “Wait until I tell my friends back home about this,” I thought.

As the professors and fellow students at Berklee agreed playing a gig every night is a sure way to get your chops together. Your speed of playing, technical facility, and ease of execution increase dramatically. As I look back on the Caribe gig, I see that it was the beginning of my morphing into a pianist rather than a trumpet player. After that summer, my piano gigs played easier, and in fact all gigs seemed easier compared to that summer's regimen.

It was nice to have some extra money, and Mike and I would usually go out to breakfast after the gig on payday. I remember it cost $1.75, and I noted that that was almost 2 per-cent of my weeks' pay! When the gig ended just before Labor Day, some of us celebrated at the top of the Prudential Building, the tallest building in Boston. I had lobster, and my bill was $9.25. I left a ten dollar bill, all the cash I had, on the table.

The very last night of the gig, Joe bought me a beer, and said he hoped to see me next summer. Then he said, “No, actually, I hope I don't see you next summer, you deserve a better gig than this!” I guess that was a compliment! With the $400 I had carefully saved by the end of the summer, I bought a new Bach Stradivarius trumpet and continued trumpet and piano studies at University of Illinois.

There's a book about the "Combat Zone" during these times that I enjoyed very much, called "Lovers, Muggers, and Thieves" by Jonathan Tudan. Click here for the Amazon link